Child Safety

Smacking is not okay

What we see in the mirror is what we can expect our children to be. Is the person we see angry, stressed, depressed or tired? Do we talk to our children, give them our time and love, and look after ourselves? What we are is what our children can become, because our children learn behaviour from us. If we hit our children, they are likely to hit their children. Children who live in abusive families are more likely to be aggressive and violent.

Most of us will have seen the Oranga Tamariki campaign aimed at "breaking the cycle". The child sits in his high chair as the parents argue and abuse each other. And the youngster who is yelled at for spilling the milk throws the stone through the glasshouse. When children are brought up in this kind of environment, they will believe that such behaviour is normal. They will believe that when you're angry and upset, you can hit out. We can break the cycle by changing the way we act and react with our children. Our own behaviour can give them positive messages that reinforce their confidence and self-worth, and it is more likely they will continue those positive messages with their children.

Smacking children is a breach of their human rights

Article 19 states: Parties shall take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse while in the care of parent/s, legal guardian/s or any other person who has the care of the child.

While this article does not explicitly mention physical punishment, it is generally interpreted as affording children protection from this kind of treatment.

Those states that signed the Convention agreed to be monitored by the International Committee on the Rights of the Child. In 1994 this committee said that physical punishment of children is incompatible with the Convention, and recommended that ratifying nations ensure that all forms of violence against children, however mild, are prohibited.

And so we can say that when New Zealand ratified the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child in 1993, a child’s moral right to protection from any form of physical punishment was internationally confirmed.

So this is why we can say that hitting children is a breach of their human rights.

Good parents – those who provide a caring and loving environment for their children – have nothing to fear from the law change designed to keep kids safe. It will not make criminals out of parents who lightly smack their children or who use physical intervention to stop children from hurting themselves or others. Despite the hysteria in some quarters, parents will not be (and have not been since the law changed) prosecuted for physically stopping children from causing a disturbance, or for picking them up and putting them in their room to “chill out”.

For good parents, it’s business as usual. The legislation is aimed not at penalising caring parents, but at keeping kids in our country safe by reducing the violence against them. It is one part of a strategy that must stop the woeful record of family violence in New Zealand. Violence is not an effective form of child discipline. The effects can have far-reaching consequences for our children, and for their future as adults. There are alternatives to hitting as a form of correction, see elsewhere on our website for effective ways to do this without violence.

There are many things a parent can do to help this process – positive actions that help the child feel safe, loved and guided. Smacking and hitting are not part of these actions. Smacking children sometimes works in the short term, but it does not contribute to a child developing self-discipline. “When we discipline children we are often trying to get the child to behave well in the short term (for example, to stop kicking the cat) and of course that matters,” Choose to Hug says. “But we should not forget that our ultimate goal is a long-term one. We want children to develop self-discipline and to grow up to be caring, confident and respectful people (who avoid hurting animals because they know it is wrong and they care about animals).” New Zealand should be known as a place where “hitting is not OK” – and that applies equally to children as it does to adults.

It is part of a parent’s role to give directions, set limits, and create consequences. This role does not entitle parents to do anything they choose with their children. People sometimes claim that physical punishment is a parent’s right. If an old person wet the bed, or knocked and broke a plate, or was rude to a family member, we would not condone hitting them as punishment. We would find it offensive and call it cruel.

So how can we justify hitting children? What can people say to themselves that make it OK?

Common beliefs when smacking children

They say:

‘’Children need to learn right from wrong. This way they get the message – short and sharp. It’s far worse to use harsh words – that’s emotional abuse’’.

Verbal emotional abuse and hitting are both harmful. They are not substitutes, and one is not better than the other.

Or

‘’It’s just part of the culture’’

A review of the research on the discipline of children carried out by New Zealand social scientists shows that ‘physical punishment does not have different effects for different ethnic groups.’ In addition, ‘there is no evidence that Maori and Pacific people are more accepting of physical punishment. In fact, one recent study showed that European New Zealanders were more likely than Maori or Pacific people to think that physical punishment of children should be legally sanctioned.

Or another popular belief:

‘’It didn’t do me any harm’’

If our children over the years become used to us hitting them and regard it as normal, what have they become? We are not brutes. We do love our children. Against our better judgement we have fallen into the habit, generation by generation, of hitting our children. For every adult that was smacked as a child and has not been negatively affected, there will people that have been affected.

Spare the road and spoil the child

The Christian faith has been particularly influential. It dominated our colonial history, was adopted by many Maori and is the faith of many of the communities that have arrived here from other parts of the world.

While the Bible may no longer be the most often read book, it continues to be quoted as a reference to express and promote values – especially family values.

Spare the rod and spoil the child. This all too familiar phrase is often used to argue that the Bible supports smacking or hitting children and that responsible parents would be failing in their duty if they did not. The specific phrase does not actually appear in the Bible but in a 17th-century poem by Samuel Butler but a literal English language-based interpretation of these verses has been challenged by many church leaders and biblical scholars.

The majority of parents want to do the best for their children. It is misguided to believe that hitting children is in their best interests. The most effective way of guiding children’s behaviour is through example. This was the way of Jesus whose life role-modelled a preference for love over violence. By contrast, hitting children endorses a pattern of violence that is passed on from one generation to the next.

Hitting does not work

In New Zealand, hitting a child is still seen by many parents as a legitimate part of parenting. The recent amendment to section 59 of the Crimes Act removed the defence of “reasonable force” for people who discipline their children by hitting them. However, a study by the Office of the Commissioner for Children showed that 2% of a random sample of more than 300 parents said they had given their child "a really severe thrashing" and 11% reported they had "hit with a strap, stick, or something similar.''

The law does not allow adults to hit each other, it does not allow teachers or others outside the family to hit children, and now children are also protected from hitting within the family. Some groups have actively encouraged hitting as a form of discipline for children, with one group suggesting that children aged seven could safely receive spankings up to 30 times a day with a leather strap. The Office of the Children’s Commissioner says no matter how hard it gets, it’s never OK to hit children.

The commissioner argues that children should have the same protection and dignity as other people in the community. Using physical force teaches children that it is OK to use violence to solve an argument, show anger or influence others. The Office of the Children’s Commissioner, the Oranga Tamariki Service and many parenting and support agencies have plenty of pamphlets and videos that provide practical alternatives to help you resolve tense situations and encourage good behaviour in your children.

This information is of value not just for parents who hit their children, it also looks at ways of encouraging positive behaviour in children and enjoying the role of parenting. It features real parents who talk about their stresses and how they feel about parenting. If there are effective alternatives, why do parents still hit their children? One argument is that physical discipline is swift and encourages instant remorse. However, if it is successful in changing a child's behaviour, the change only occurs because the child is fearful of being hurt.

In some cases, especially small children, they might not even know why they are being hit. If hitting is intended as a lesson, it cannot be effective if children become fearful and resentful. Hitting also tends to have a reduced effect the more it is administered. The more a child is hit, the less effective it becomes, and the more likely it is that a parent will hit harder to get the desired reaction. Hitting is not only a response to a "naughty" child but is also often an outlet for a parent's frustrations.

The stressed parent who is not coping well with work or the lack of it, with a relationship or whatever, can often strike a child without the child having done anything wrong. In some cases, the hitting is sustained and brutal, leading to long-term injury, psychological and emotional harm, and even death. Some of these children are not even old enough to know what the parent considers right or wrong. The alternatives to hitting require patience, but the rewards are worth the effort.

Alternatives to hitting, yelling and put-downs

Hitting a child as a form of discipline or to correct behaviour is not only ineffective and harmful, it is also illegal - just as it is illegal to hit another adult. But hitting is not the only way we can harm our children. We can hurt them with words said in the heat of the moment - swearing, yelling and putting them down as people in their own right. We can also hurt them by fighting and arguing in front of them. Research shows the effects of emotional and psychological abuse can be just as harmful and long-term as physical abuse. In such circumstances, our children grow up to believe that abuse is a means of solving problems. Can we blame them if, when they grow older, they want to take out their frustrations with us in the same way? Many teenagers grow up to abuse their parents, but worst of all, they become adults who repeat the cycle with their children - your grandchildren.

Children are just human beings who have not grown up yet. They have much to learn, and as parents, we can teach them a great deal. We can teach them that some behaviour is not appropriate. We might get them to change their behaviour with hitting and verbal abuse, but this will only make them abusers themselves. Verbal abuse and hitting might change a child’s behaviour, but it will only be through fear. Some of the side-effects for children will be:

- Fear, including fear for others

- A feeling of worthlessness leading to self-criticism

- Self-blame and feeling responsible for being hurt or others being hurt

- Taking it out on others with bullying and other anti-social behaviour

- Anxiety, depression or withdrawal

- A need to act like a parent, caring for other children or parenting the parent

Apart from the fact that the recent amendment to section 59 of the Crimes Act does not allow us to hit children, we have a responsibility to use alternatives. So we must use alternatives whenever possible. The first thing we can do when we are tempted to hit a child is to stop and think about whether it is something the child is doing that’s making us feel angry or upset. The sound of a child playing at the end of the day when we feel exhausted could get on our nerves, but it is not the child’s behaviour that is to blame. If we pause to think first, we might find that the child has nothing to do with how we feel. In such cases, either deal with what is causing you to feel the way you are or take yourself or the child out of harm’s way while you cool down.

There’s a saying in carpentry: “Measure twice, cut once.” In parenting, we might need to think twice before doing something that cannot be undone. If we make a mistake, we must be “adult” enough to admit it and apologise to our children. They will respect us more for it and are likely to have more compassion for us when things get rough. In some cases of misbehaviour, it might even be appropriate to do nothing. We might not like what the child is doing, but if it is not hurting anyone, it might be best to ignore it. Sometimes, children will find out for themselves that what they do is not appropriate. Behaviour can sometimes be self-correcting. If a child fails to put clothes in the laundry, for example, they have only themselves to blame when their clothes are not clean the next day. When we do need to deal with a child’s behaviour:

- Keep calm.

- Recognise that it’s OK to be angry, but focus on the behaviour, not the child.

- Use positive messages, reinforcing what you want them to DO, not what you DON’T want them to do and be clear about the behaviour you want, ie: “Keep your toys in your room”, not “Don’t leave your toys lying around”.

- Tell your child without yelling or screaming. Give the message that the behaviour is bad, not the child. If you want the child to change their behaviour, you will need to provide some guidance. Tell them what they did wrong and what you expect next time.

- Let them do some of the talking and listen to what they say. They might have a good reason to feel they are being picked on.

- Try distraction. Give the child something else to do like playing a game i.e, I spy, The Alphabet Game, or I’m going on a Picnic.

It’s a great way of easing the tension for both of you. If you need to correct behaviour, try emphasising that the behaviour will have consequences, such as withdrawal of a treat or privilege. Be clear about why it is being taken away and for how long, and stick to it. “Time out” might be a useful technique for a child who needs somewhere safe and quiet to calm down and regain control. The Office of the Children’s Commissioner, however, says that often it is parents who need a chance to calm down and regain control while the child is in a safe place. “Time out” should be used with care, and not misused as a form of punishment. In the booklet Choose to Hug, the Commissioner suggests “time out” should never be used:

- as a punishment or threat

- for more than a few minutes at a time

- if there is nowhere safe for the child to be

- if the child is not mature enough to understand why he or she is in “time out”

The following are important guidelines, the booklet says:

- the child should never be locked in

- the child should never be restrained (forcibly put in “time out” or held down in any way)

- a place that should be peaceful and safe for a child (like a bedroom) should never become associated with anger and fear; “time out” should never be used in a way that leaves the child feeling distraught, rejected or abandoned – a small out-of-control child is very frightened and overwhelmed by their feelings

- the child should always understand that they can come back to you for reassurance when they have calmed down

Child safety tips

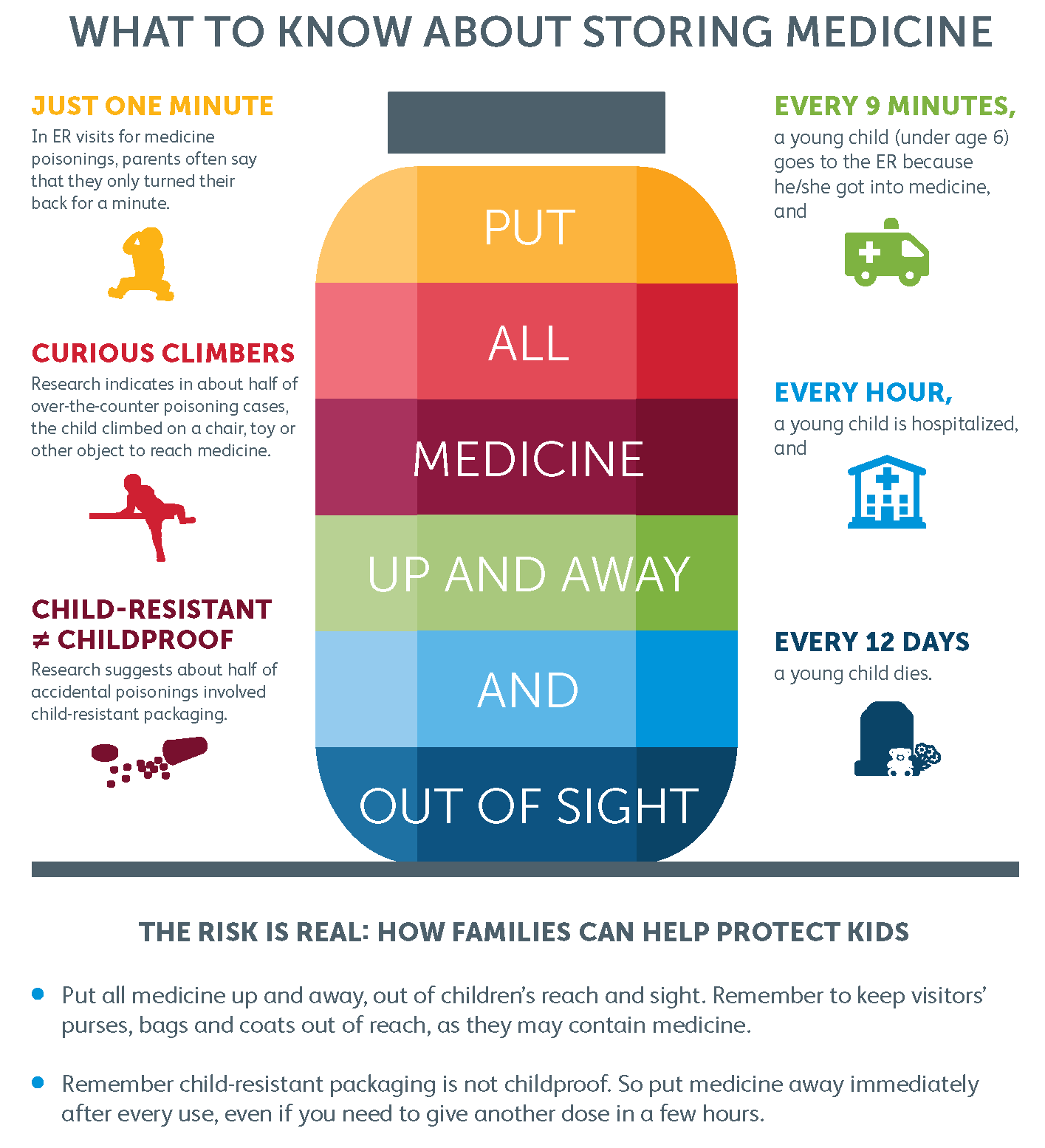

To help keep your children safe, check your home environment and family safety procedures. About 13,000 children aged under 5 are hospitalised each year because of accidental injuries and poisonings. If you keep your children safe many of these accidents and injuries are avoidable. For example, have you:

- Taught your child not to leave the property without a trusted adult?

- Taught your child to hold an adult's hand when stepping onto the road?

- Fenced the outdoor play area?

- Made sure the garage, driveway and work areas are not accessible?

- Hired a babysitter who is at least 14 years of age and left written instructions, including a contact number (see the section on babysitters).

- Checked safety aspects of your childminder's home or childcare centre?

- Installed safety catches on windows above ground level?

12 general child safety tips:

- Never leave a young child alone while he/she is awake. Check on the child occasionally while they are sleeping.

- Never leave a baby unattended on a changing table, in a high chair, bath or walker. Use safety straps whenever they are available.

- Stay awake so you'll hear the children if they need you.

- Children will likely try you out to see how far you let them go. Be firm in insisting that they play where they will be safe.

- Wardrobes, medicine chests, drawers and storage locations are not proper places for children to play. Also, keep them away from stairways, hot objects, (such as iron, stoves, microwaves and electrical outlets).

- Keep scissors or knives out of sight.

- Keep buttons, pins, cigarette stubs, money, small toy pieces, matches and any other small particles off the floor and out of sight.

- If playing outside, know where their parents allow them to play. Watch for traffic and fire hazards, garden sprays, tools and unfriendly animals.

- Cut food into bite-size pieces for toddlers and preschoolers. Make sure that children remain seated while eating. Avoid foods that are likely to cause a young child to choke such as popcorn, hot dogs, hard candy and grapes.

- Make sure that doors to rooms such as bathrooms, basement and garage are closed.

- Remove plastic bags, bean bags or pillows from cots. These could cover a child's face and cut off breathing.

- Remove any strings or straps that might pose a strangulation hazard to a young child.

Bathing children

- When you bathe children, do it very carefully and never leave the child alone in the bath.

- The water in the tub should be comfortable to touch, not too hot!

- Always run the cold water first. Test temperature three times.

- Keep the bath plug out of reach. One child’s life could be saved each year if everyone did this.

- Use hot tap cover.

- Keep all electrical cords from appliances out of child’s reach.

- Keep all containers of hot liquids well out of a child’s reach.

Toy safety

It is important to have separate play areas when you have a number of children. What is suitable for a five-year-old could be lethal for a toddler. Rule of thumb - If it is small enough to fit into a film canister then it is too small for a child under three years of age to play with. Some tips for child safety:

- Put away toys with objects small enough to swallow when watching a child under age four.

- Put away toys with sharp edges and sharp points as well as toys that shoot objects.

- Look for toys with long strings and chords that may strangle an infant or young child. Put these toys in a place where young children cannot reach them.

- Buy toys suitable for a child’s age.

- Check for warnings and the labelling on toys.

- Develop a system of regular checks for wear, broken pieces and sharp edges.

- Check soft toys and dolls for loose parts e.g. eyes, buttons, and noses.

- Balloons are only to look at, not for baby’s play.

- Small balls, marbles, etc are a choking hazard.

- Keep cots clear of toys, especially for babies.

- Toys that are noisy may affect a child’s hearing.

- Make sure toy boxes have a lightweight lid and can easily be pushed open from the inside. For extra safety, drill ventilation holes in toy boxes.

- Ensure that toys are kept away from traffic areas, especially stairways and doorways.

- Encourage children to put their toys away after play.

- If you have a very young child, get down to their level and check that no small objects are hiding under settees or low tables.

- Remember in all cases - supervision is essential.

- Put away electronic toys that might burn or shock young children.

Pet safety

Remember when you decide to have a family pet you are making a long term commitment to care and responsibility of a dependent member of the family. Think about it carefully. Never impulse buy a pet - seriously consider your reasons. Consider the type of pet suitable for your family.

- If renting - are animals allowed.

- The maturity and temperament of your children.

- The temperament of the animal.

Pets need a loving home, regular food and water, shelter, security, plenty of exercise and a fully fenced section.

- Can you provide the above?

- Financial costs involved: food, vet bills, vaccinations, flea and worming treatments, dog licensing and toys.

- Teach children not to disturb animals when they are eating

- Don’t disturb cats and dogs when they are sleeping.

- Wait for a pet to come to you.

- Teach children how to handle their pets - remember pets are at risk from children who have not been trained.

- Never put your face near your dog.

- Always clean up after your pet, it cannot do this for itself.

- Ensure practice of handwashing after play with animals.

Sometimes children and pets do not get along! But just as there are good and bad ways to behave with people, there are good and bad ways to play with animals. With strange dogs always be alert to signs of aggressive posture in a dog. Erect ears, stiff body and raised hackles (hair on the neck).

Young children especially can receive nasty bites from dogs that are not properly under the owner’s control. If your child is bitten, see if the dog has a collar or tag and take note of the direction the dog went. Wash the bite with soap and water and see your doctor at once. Report the dog to your local authority’s animal control division.

Ten rules for child safety with dogs:

- Never go up to a dog you don’t know.

- If the owner is there, ask permission to pat the dog.

- Don’t stare at a dog. It may see this as a threat.

- Don’t tease dogs. It may make them angry.

- Don’t go near a dog when it is eating. It may think you’re trying to take its food away.

- When going onto a strange property, don’t go in if the dog is growling or barking. Dogs naturally want to protect their property.

- When stroking a dog, rub its chest and don’t place your hand on the back of its neck because the dog may see this as a threat.

- Mother dogs are very protective, so don’t touch the puppies unless the owner is there.

- Do not disturb a sleeping dog by touching it. Wake it up from a distance by making a noise.

- If a strange dog approaches you, act like a tree - stand still. If carrying a bag, or have a bike, put that between you and the dog. Don’t ever lie on the ground to protect yourself. If carrying food, drop it. If a strange dog approaches you and you are lying down, or the dog knocks you down, curl up like a ball and cover your head, then act like a log - lie still. The dog will not see you as a threat, and it should go away after it smells you.

- If you have any problems tell your teacher or parent to report the problem to the council’s animal control officers.

List courtesy of Hutt City Council Animal Control division.

Outdoor safety

Explain your outdoor rules to children. Your list might include: no pushing other children off a swing or piece of playground equipment, no swinging empty swings, no climbing up the front of the slide, no twisting swing chains, no rough playing on equipment, and only one person can be on a piece of equipment at one time, if it is designed for use by one person.

Children are usually unaware of the risks that are present in playing outdoors. You can teach them to play safe when they are playing outside.

- Keep children from walking in front or back of a moving swing.

- Place young children in the centre of a swing. Make sure that they are capable of hanging on to the swing or place them in a swing designed for infants and toddlers. Keep reminding them to hang on - small children need constant reminding.

- Be extremely cautious of swimming pools, paddling pools, and spas even when a pool has a cover and is fenced in. Keep your eyes on the children at all times. If a child is missing, immediately check the pool to make sure the child has not fallen in it.

- Make sure the gates are locked, and paddling pools are emptied after use.

- Learn CPR and first aid practices in case you might need it when watching children.

- Learn the phone number for emergency medical services in your location.

Get your kids safely home

Teach your child how to get safely to and from school – whether they walk or bike or go by bus. Make some firm, clear family rules. Go to school with your child so that you can show them the safest route. Train them to deal with hazards such as narrow footpaths or busy roads. If they walk, make sure they always use pedestrian crossings.

Who does your child walk home with? Meet the parents of children in your area, and keep in touch. Train the children to walk home together in twos or small groups and not alone. If someone is away, make other arrangements.

It is the parents' responsibility to teach their children about keeping themselves safe. There are good books and videos available. You don't want to frighten your child. Ask the teacher about programmes provided by the school – schools teach many safety programmes, including Keeping Ourselves Safe.

When children are visiting friends after school, always arrange it yourself. Check with the friend's parents before school. In-country schools, tell the teacher, too.

Babysitter guidelines

As a parent, you are responsible for your child's safety and well-being. You often need a break from those responsibilities so you need a babysitter you can trust babysitting your child. Right? Unfortunately, not all parents appear to take such precautions.

Cases, where parents have left their children without any proper care, is all too frequent. Under the law, parents and caregivers are responsible for supervising or arranging suitable supervision for children at all times up to the age of 14. Section 10B of the Summary Offences Act 1981 states you cannot leave a child alone without reasonable supervision and care, for a time that is unreasonable or under conditions that are unreasonable.

It does not mean literally that you must not leave a child aged under 14 alone. It might not be "unreasonable" to leave a child who is, say, aged 13, mature and trustworthy, and where a neighbour is advised that you are out, and in a case where you will not be gone for long. The Police take cases seriously; where children are left for long periods of time - having to cook meals, look after small children and generally fend for themselves.

If you need to leave your children for any time, make sure they are being looked after or looked out for by someone capable and trustworthy. Children are vulnerable and trusting - don't leave them with just anyone. If you have doubts about a neighbour or even a family member, don't use those people as babysitters. When you need to call in a babysitter you don't know, find out something about them first. Invite them over when you are there for the first occasion, so you can introduce the children and get details without having to rush out the door.

Good babysitters are safety-conscious and take extra precautions to make sure the children are safe from accidents. If you need to talk on the phone, make sure you always know where the children are. Make calls short and always be attentive to the children.

Questions to ask yourself before you choose a babysitter:

- Is our babysitter mature enough to deal with more than one child in a crisis situation?

- Does our babysitter have experience in dealing with distressed children when babysitting?

- How long will it take us to return home should there be any crisis that our babysitter is too young to deal with?

- Have we made and practised with our family an escape plan should there be a fire?

- Practising the exit drill (see separate section on fire safety) can be a fun activity for the babysitter and the children.

- Have we listed contact names and numbers for my babysitter? i.e. Doctor, Fire Service, Neighbour, Parents, Ambulance, Police.

- Does our babysitter know where we keep the following items? i.e. Torch, First Aid Box, Telephones, Light Switches etc.

- Have we installed smoke alarms and do we have safety latches on outside doors?

- Have we made sure all hazards i.e. drugs, medications etc are safely stored?

- A young babysitter will not be alert to the dangers many things pose for young children.

- Is it right to give adult responsibilities to a child?

- Make sure they know where they can contact you and what to do in an emergency.

- If any of the children are on special medication, ensure the babysitter knows how to administer it if necessary.

- Make sure the house is secure when you leave, checking all doors and windows.

- Tell the babysitter not to open the door to strangers.

- The babysitter should tell telephone callers that you are not available, not that you are out and that they are alone with the children.

- Be sure the babysitter gets home safely - don't let them walk home on their own in the dark.

Sudden infant death syndrome

Sudden infant death syndrome, or cot death, is the unexpected death of a child that cannot be explained through autopsies and investigations. SIDS claims 80-100 lives every year in New Zealand. However, cot death numbers have reduced dramatically in New Zealand over the past 15 years. This decline is attributed to the findings of the New Zealand Cot Death Study, conducted over three years. The study's aim was to identify risk factors for SIDS. New Zealand was the first country to launch a SIDS prevention campaign in 1991. The main advice given by the Ministry of Health and the New Zealand Cot Death Association to prevent SIDS is:

- Do not smoke during pregnancy.

- Avoid smoking in bed with your baby or near your baby.

- Sleep baby on his/her back.

- Breastfeed your baby if you can.

- Give your baby his or her own sleeping place, not in bed with you.

To help your baby sleep soundly, follow these guidelines:

- Put the baby on its back to sleep

- Keep the baby's head uncovered, with the feet to the foot of the cot and with baby's face clear at all times.

- Use a firm, clean, fitting mattress with no gap between the mattress and the cot side.

- Tuck in all bedding securely.

- Never put the baby on a waterbed and pillows.

- Soft toys, loose quilts or duvets are not recommended.

- Keep baby's room temperature about 15-18C.

- Check your baby often.

Baby Blue Syndrome

Studies show a link between consumption of nitrates in drinking water during pregnancy and both preterm and underweight births. Nitrate levels above 5mg/L increase the odds of a preterm birth (20 to 31 weeks) by 47 per cent, while exposure above 10mg/L increases the odds of a preterm birth by 2.5 times.

Consuming too much nitrate can be harmful - especially for babies as it can affect how blood carries oxygen and can cause methemoglobinemia (also known as blue baby syndrome). Bottle-fed babies under six months old are at the highest risk of getting methemoglobinemia.

Nitrate in drinking-water

Nitrate is a naturally occurring organic compound that contains oxygen and nitrogen atoms. It can be found in low concentrations in water and soil. Nitrate is vital for a healthy environment. Nitrate has no detectable colour, taste, or smell in drinking-water.

If your drinking-water comes from a private bore then nitrate may be present in it. You are responsible for testing your bore water to ensure it is safe.

If your drinking-water comes from rainwater then you do not need to be concerned about nitrates. Find out how to keep your rainwater safe in ESR's Household water supplies manual.

If your drinking-water comes from a council or community water supply then the supplier is responsible for monitoring the water. They must test for nitrates if they have been found to be present at levels above 25 mg/L in the past.

Potential effects of high nitrate levels in drinking-water.

Using drinking-water that has nitrate levels above 50 mg/L can cause methemoglobinemia (blue-baby syndrome) in bottle-fed infants. Children under six months are most vulnerable.

Nitrate can be reduced to nitrite in the gut of an infant. It is then absorbed into the blood where it interferes with oxygen transfer. This gives the infant a blue colour, especially around the eyes, lips, and fingers. Other symptoms of blue-baby syndrome include headache, tiredness, and shortness of breath.

An infant with blueish skin should be taken to a doctor immediately. If you are pregnant, high nitrate levels may reduce the amount of oxygen getting to your baby.

There is a higher risk of blue-baby syndrome if the infant has a stomach bug. To reduce the risk of illness, you must make sure that drinking-water used for infants is free from harmful bacteria and viruses. Until your baby is at least 18 months old, all bore water used for formula should be boiled and cooled to room temperature on the day you use it. This will kill harmful bacteria and viruses – but will not remove any nitrates.

- Get more information about preparing safe water for infant formula

- For more advice on blue-baby syndrome call Healthline free on 0800 611 116

Testing drinking-water for nitrate.

You will need to collect a sample of your drinking-water and send it to an accredited laboratory for testing. You can get a testing kit and instructions on how to take samples from the laboratory. Your local public health unit can give you details for the nearest laboratory, or search the full list of accredited laboratories in New Zealand. You should regularly test your water for nitrates because levels change frequently – at least once per year.

What to do if your drinking-water is high in nitrate.

Pregnant people and infants under six months old should not drink water that has a nitrate level above 50 mg/L.

If a test shows that the nitrate level in your bore water is close to or above 50 mg/L you need to treat the water or use another water source. Common methods such as boiling and disinfection do not remove nitrates.

A small treatment unit called a "point-of-use device" can be installed under your kitchen tap to remove nitrates. Ion exchange and reverse osmosis are the best point-of-use devices for removing nitrates from drinking-water.

- Ion exchange devices pass your water through a tank filled with resin that absorbs the nitrate, providing water with over 90 percent of nitrates removed.

- Reverse osmosis uses pressure to force water through a filter that removes most of the nitrates.

- Get more information about these devices in ESR's Household water supplies manual.

These devices are expensive, so you should first consider if there is a better alternative water source for you to use. Bear in mind how long the device will operate before parts need replacing and how much that will cost. Equipment manufacturers and suppliers can tell you how long the equipment will last and how to keep it working effectively.

Find more information about protecting your bore from contamination in HealthEd's pamphlet Secure Groundwater Bores and Wells for Safe Household Water.

The Smoke-free Environments Amendment Act

To limit children’s exposure to second-hand smoke, it is now illegal to smoke and vape in a vehicle that has rangatahi and children (under 18 years old) in it - whether the vehicle is moving or not.

The Smoke-free Environments (Prohibiting Smoking in Motor Vehicles Carrying Children) Amendment Act was passed in May 2020 and came into force on 28 November 2021. This prohibits smoking and vaping in motor vehicles carrying children and young people under 18 years of age.

Smoking (or vaping) in a vehicle carrying a child occupant may result in the individual being liable for a fine of $50, or a court can impose a fine of up to $100.

Children can’t get away from the smoke in your car. Opening or winding down the window doesn’t remove all the poisons in second-hand smoke. The poisons will stay long after the smoke and smell have disappeared.

There is lots of evidence about the harms of second-hand smoke.

- Children who are exposed to second-hand smoke are more likely to develop illnesses such as chest infection, glue ear and asthma

- Exposure to second-hand smoke increases the risk of sudden unexpected death in infancy

- Young people who have friends or whānau who smoke are more likely to become smokers.

- Younger children/babies are particularly vulnerable to the effects of second-hand smoke exposure due to their smaller lungs, higher respiratory rate (they breathe faster), and because their immune systems are still developing.

Firearms and children

New Zealand law requires gun owners to have a firearms licence issued by the Police. Recent incidents have shown how dangerous guns can be in the hands of children.

- Firearms should always be kept out of reach of children.

- Ammunition should be stored separately from the gun.

- The gun should be disabled by removing the bolt or firing mechanism and stored separately.

- Gun owners must have a lockable store for guns at home.

- The firearms must always be locked there unless under the immediate supervision of the licence holder.

- Guns should never be left out unattended.

The Police issue a firearms safety manual which lists seven basic rules for gun owners:

- Treat every firearm as loaded.

- Always point firearms in a safe direction.

- Load a firearm only when ready to fire.

- Identify your target.

- Check your firing zone.

- Store firearms and ammunition safely.

- Avoid alcohol or drugs when handling firearms.

Safety on Halloween

There are always risks when small children are on the streets without adult supervision after dark. These risks can be minimised by careful planning.

Halloween party: Consider celebrating by holding a children’s party in place of trick and treating.

Trick or treating: Take place before dark with an adult accompanying the children. Choose the area carefully, children should only call on homes where the residents are known to you and that have outside lights on indicating that they are expecting you to call.

Pedestrian safety: Supervision is essential. All children should WALK from house to house, staying on the footpaths and be warned against crossing the road from between parked cars or from where they cannot see oncoming traffic. Watch for traffic coming in and out of driveways.

Clothing: Costumes should be close fitting, brightly coloured and short enough so as to avoid tripping. Some tips:

- Decorate or trim costumes with reflective tape, this not only gives a more ghostly appearance but also glows in the beam of cars lights, enabling better visibility to motorists.

- It is advisable for children to carry a torch, to see and be seen.

- Headgear, masks and wigs should be close fitting to minimise the risk of slipping and affecting vision, eyeholes in masks need to be large enough to allow full vision.

- Accessories, swords, knives, wands etc, need to be made from flexible materials.

- Footwear should be sturdy and fitting properly. Avoid high heels (they may look good but could be dangerous on uneven ground)

At home: If using lighted candles, place them away from traffic areas and well away from curtains, decorations, paper streamers and spider webs. Spray string/streamers are highly flammable. Make sure pathways are clear, outside light is on and pets are in a safe place for the children that will visit your home. Have a safe and happy Halloween.

Never leave children in a car without an adult

Do you know that the temperature inside a parked vehicle can be as much as 50% hotter than the outside temperature? Lowering the vehicle windows 5cm does not bring about a dramatic loss of heat.

75% of the increased temperature happens within 5 minutes of closing the vehicle and leaving it. The larger the expanse of glass in the vehicle, the faster the rise in temperature. The colour and size of the vehicle can have a bearing on the rate at which the temperature rises.

- Always carry plenty of drinking water, we suggest that each child has their own drink bottle

- Dress children in lightweight, light-coloured, and loose-fitting clothing - thus enabling airflow around their bodies.

- Check safety belts and harness fitting, this may need adjusting due to wearing lightweight clothing.

- Consider fitting removable sunshades to filter the sun rays, these do not hamper airflow and allow children to travel more comfortably.

- Every 2 or 3 hours, stop and allow children time for play and exercise.

- If travelling with a baby, allow them time on a blanket to move freely.

- Always plan car trips in advance and consider travelling in the early morning or late afternoon when it is cooler.

As the temperature rises a child will begin to suffer hyperthermia and get dehydrated. As the temperature rises so does the humidity and the airflow decreases. Young children are more sensitive to heat stress - the younger the child the faster the onset of dehydration. Hyperthermia, dehydration and asphyxia can all lead to death.

Animals can also suffer heat stress when confined inside a vehicle.

Safety first:

- Before leaving your parked car, remove all clothing, hats and paper products from the rear parcel shelf and the dashboard. Store away from direct sunlight.

- Remove from the car cigarette lighters and any aerosol or LPG canisters. (These have been known to explode and other articles burst into flames.)

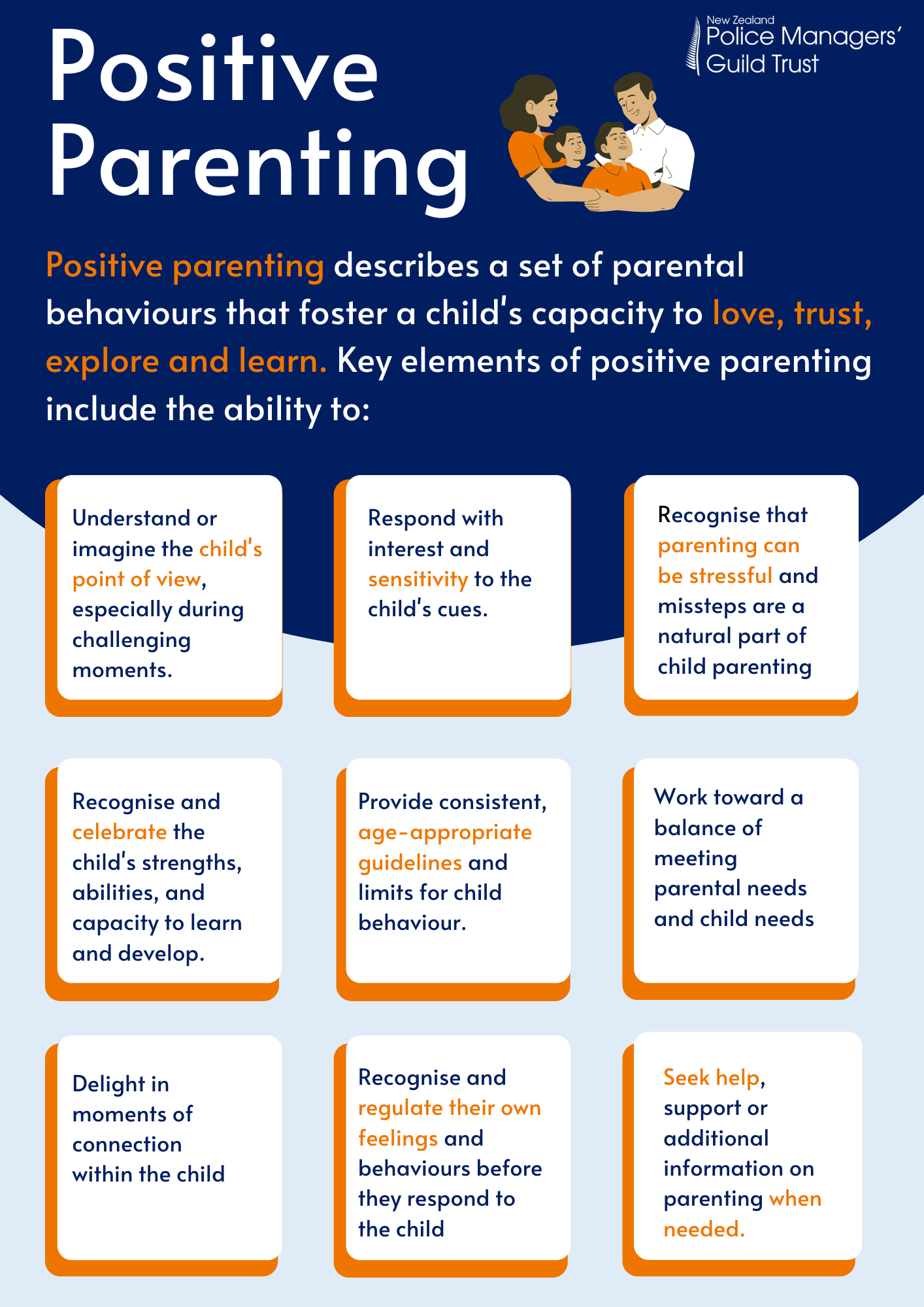

Positive parenting

Being a parent is an awesome responsibility but one which is enormously rewarding. When people become parents they get a unique opportunity to encourage and inspire a new generation of adults who care about themselves, others and their environment, thereby creating better and safer communities for all. Families, whether big or small, one parent or two are at the core of our society.

Values and attitudes that prevail in homes are the same values and attitudes, which will prevail in our communities. This is why the Police Managers' Guild Trust believe it is important that parents receive positive information that will help them not only become better parents but to also enjoy the experience much more. This information is not intended to be a manual for parenthood, because parenting can never be “done by the book”.

However, it is designed to have many helpful tips, which might help you develop yourselves as a positive role model for children. It might also help you cope with the inevitable stresses that come with parenthood and give you more time to help your children with the care and attention they need and deserve. If we have safe happy families we have safe and happy communities. All parents want their children to grow up in a safe environment.

The Police, welfare agencies and many other groups help to make the community safe for children with education and enforcement programmes, but parents ultimately have the greatest role to play. It offers constructive advice and tips to help parents create a happy, safe home, and perhaps more importantly, it helps parents show their kids how they can act responsibly and be safe away from home.

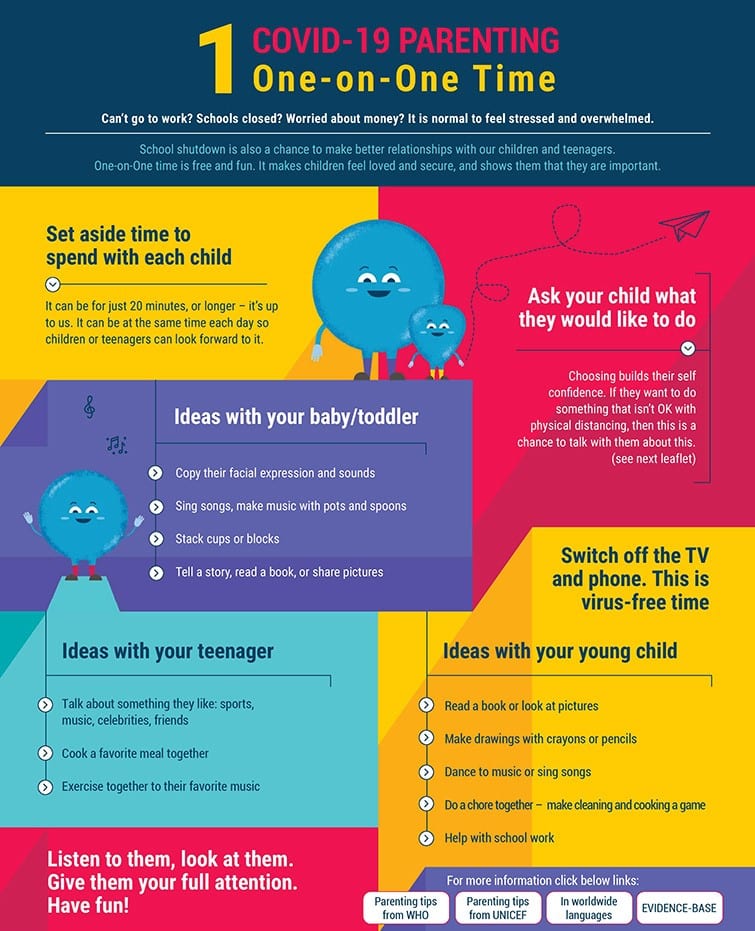

However, if there is one piece of advice that all parents should take on board, it is simply to talk to our kids. Communication is our most valuable tool. If we spend regular time with our kids and make sure we talk with them, we can understand them better. And they might just get to understand us better.

That is the goal with our community safety/crime prevention campaigns. We all need to “walk the walk” and present positive role models. We can only expect our children to do as we do; not do as we say.

Parenting is also a lot of fun if we allow it to be. Often we feel powerless to change behaviour that we see as “bad”, or we feel frustrated at children who won’t “do what they’re told”.

However, parenting is a responsibility that requires great care and patience, and none of us wants to get it wrong. If we have the fortune or foresight to have a planned child, we have a good start. We can then think about what we are getting ourselves into before committing ourselves. What adjustments will we need to make to our lives? Who is going to look after the child, when modern society often demands that parents must work to survive? Do we really know enough about children to take on this responsibility? And do we know enough about ourselves? Can we cope when life might seem tough already?

Is there a good reason for having a child - it must never be seen as a solution to relationship problems that are already under stress, for example. Even if a pregnancy is unplanned, we can still prepare for the future of our child, so they come into the world loved and wanted. Good planning can reduce some of the inevitable stresses of parenthood.

We can’t get it right all the time

No parent can do everything right all the time. If you have a friend or relative that you admire as a parent, try asking them how they do it. Most likely they will tell you that they don't believe they are doing it right, that they are always having problems with their children in one way or another. All parents want the best for their children. It might seem ironic in the case of a parent who abuses his or her child, but it is simply an extreme example of a parent who gets things horribly wrong. We can love but still cause such terrible hurt to our children - sometimes without realising it. If we want the best for our children, why don't we do our best? Is it because we see our children simply as possessions with whom we can do as we wish? Is it because we don't give them enough time out of our busy day? Is it because we don't talk to them? Are we too "adult" to say that we love them every now and then? It's OK when we try, but still, don't seem to get it right.

The value is in the effort, and the rewards might not be obvious straight away. But a kind word when previously there was a harsh word can work wonders for a child's confidence and the parent/child relationship. We're not alone in the parenting world of hard knocks and we can't spend our lives trying to prove to ourselves or others that we can do it all. Anyway, there is often no "right way", because parents and children are individuals, and have individual needs. What we can do is become more aware of how we can become better parents and begin to apply some useful tips. We can read information such as this and others available from help agencies; talk to other parents, educators, friends and relatives; attend parenting courses, and observe those parents we admire.

With parenting, there are no typically good or bad parents

Good and bad parents exist in all cultures and socioeconomic environments. Money, for instance, does not guarantee better parenting. It just means that the issues are sometimes different. If a child is being neglected in an area of great poverty because parents are out of work, or if a child is being neglected in an area of great wealth because the parents are always at work, the neglect still exists. The result is likely to be the same – a child who will run off the rails. Good parenting is not something that can be bought.

Good parenting is an attitude. It is unconditionally caring for a child simply because you are responsible for that child. It is still caring when the child gets into trouble or is disobedient. Parents sometimes blame their apparent lack of parenting skills on their environment or circumstances. “I have to work all day and I’m tired out at night”; or “I never have the money to do anything for the kids”. The stresses of life are undeniable, but if we want to be better parents and change life for the better for our children, then we must make the change ourselves. It is likely to be a change in us, as parents, that will bring about a change in our children. Try:

- thinking about what you are doing

- thinking about what harm you could do

- putting your child in a safe place if needed

- phoning a friend or someone you trust

- putting on some of your favourite music (preferably calming music)

- thinking about joining a parenting course – it will give you lots of ideas and methods of coping

- figuring out why your child is misbehaving

- hitting a pillow if you’re still mad (out of sight of the child).

If we are struggling to give our children our time and love, we must get help. This is a key message of this crime prevention website. There is no shame in asking for help. Parenting is not easy and no one expects you to do it all on your own. We all need help sometimes - for families who have children with special needs, it might be that we need help all the time. Don't be afraid to ask. There are many agencies, both Government and private, that are available 24 hours a day to help parents. Some organisations have 24-hour phone numbers that you can ring - maybe you just want to get a problem off your chest, or you need to know where you can get further help. There’s a list of these on our website. Your greatest source of help, however, might be someone you know on a more personal level - a friend, relative, neighbour, teacher, or counsellor. They can help you make decisions and give you perspectives that you might not otherwise see.

Positive messages

Children will not be “good” all the time, but we need to ensure they are aware of good behaviour. Be positive when you talk to your children about their behaviour. Take time to think about what your rules and values are and then make sure your child knows them. Tell them why those rules and values are important. Don’t expect your child to follow rules that are not adequately explained. Thank them for their efforts, even if they sometimes get things wrong. Look for things your child is good at and comment on it. Often we fail to see the positive side of children. Recognise that they will sometimes fail to do things right, even when they try hard. It is only a learning process, so be supportive. Never put a child down for trying. Show an interest when good behaviour is happening. Give hugs and smiles. Save the tangible things like lollies and toys for birthdays or other special occasions. Give children confidence in themselves by letting them make some decisions that affect them, ie: “Would you prefer the red dress or the green one today?”

It’s okay to be angry

The strategies outlined on this crime prevention website are not designed to stop you getting angry. Anger is a natural response – a child needs to be aware that some things will make you angry and upset. It is how you manage your anger that is important. Hitting, yelling and being abusive is not a healthy response to bad behaviour. Tell your child that you are angry, make sure they know why you are angry, and make sure they know what you expect from them in future. Direct your anger at the behaviour, not the person. It is not the child that you do not like, it is the behaviour.

Healthy parents, healthy children

If we look after ourselves, we have a greater chance of coping with stress and looking after our children well. Healthy parents, healthy children. If we can balance our own health and wellbeing with other elements of our life such as work, pleasure, relationships and personal growth, we have a good chance of dealing with the challenges that are thrown our way. Are we too busy to look after ourselves? Do we put the balance out of kilter by working too much, for instance, and not devoting any time to ourselves? Again, if this is what we show our children, this is likely to be what they will copy. Do we want them to grow up believing work is all that is important? We must make time for ourselves. If we are bringing up children alone, we especially need time out. Ask friends and family to help look after the children when you need time for yourself - and not just so you can do the shopping or complete chores. Sometimes you will just need a break to relax alone. Keep in touch with friends, join groups and get involved in activities outside the home. If you have a partner, nurture the relationship. Sometimes the best thing a child can have is parents with a stable and loving relationship. Make time for your relationship, as you do for your children. Share the load of parenthood and discuss how you might better cope with the stresses together.

Enjoy parenting and congratulate yourselves regularly for what you are achieving with your children. Share your children's achievements as a family. An Oranga Tamariki booklet called, ‘There are No Super-parents’ suggests parents who feel good about themselves:

- Play with the children and set aside family "happy times".

- Have supportive family members and community networks.

- Have a goal in life.

- Do some sort of regular exercise.

- Have hobbies.

- Get a good feeling when they do well.

- Accept that small mistakes happen from time to time, and learn from them.

- Provide healthy food for their family.

- Look for ways to get the best out of people, instead of concentrating on their faults.

Get involved

New Zealanders have always been proud of their sporting prowess and "give-it-a-go" attitude. Now more than ever, however, it is recognised that participation in sport and leisure activities is good not only for the individual but also for the community. People involved in regular sport or leisure activities get fit, generally have healthier lifestyles, meet people, find a sense of value in fair play, set goals, enjoy the outdoors. Though time is often limited, it's well worth the effort of joining a local sports group or just getting some regular exercise out walking with a friend. Such activities give you the opportunity to get away from the stresses of home life and help you better cope with them when you get back. Make time for leisure. Work out with your partner how much time you will spend away - and whether it will involve social activities after the game or walk. You might have to compromise so you both have a chance to participate. Think about coaching or refereeing sports teams. Most clubs and organisations will provide training. Consider also social and cultural activities. Expand your mind as well as your skills and self-esteem by joining a local drama group, an ethnic group or a book club. Ask around or visit your local community centre to see what activities are in your area. Making contacts through community or sports groups can be enormously valuable. You will find new friends, perhaps someone to confide in when you need to, someone who might get you a job or one better than the one you are in now… the possibilities are endless.

How to tell if you’re not coping

The Oranga Tamariki booklet, ‘There are No Super-parents’ says it's normal to have bad feelings every now and then. However, when they seem to be taking over, it's time to talk about them and ask for help. The warning signs that tell us it's time to slow down, take a break or ask for help can be:

- If you have more bad feelings than good, and they seem to be lasting longer and getting stronger.

- If you can't face getting out of bed in the mornings - a real dread of coping with the new day.

- If you cry more than usual and you feel confused about this.

- If you have feelings of anger, panic or despair when the baby cries and you feel like you might lose control and hit the child or try to hurt them.

- If you can't think of any fun things to do with the child. You feel too depressed and exhausted.

- If you feel utterly trapped and alone and can't talk to anyone because no one understands.

- If you think the child would be better off without you.

- If you feel anxious and then angry when the baby cries.

- If you and your partner are arguing a lot or fighting.

- If your partner leaves you alone to cope when you have problems with your children.

- If you feel angry when the child dirties a nappy.

- If you feel one of the children is especially bad.

- If you are afraid to be alone with your child.

- If you feel there are times when you can't cope and have no one to turn to.

- If you feel the children demand too much when you get home from work

- If you leave the house when the children are arguing or crying.

Oranga Tamariki also says fathers especially should recognise warning signs such as:

- If you find it hard to show any feelings except angry or sexual feelings.

- If you feel you're only a money machine that must grind on.

- If you'd rather go to the pub than go home and face the kids.

- If you feel it's not your job to help your partner change nappies or do the housework.

- If you feel it's your partner's job to look after the children.

- If you are hitting or hurting your partner or children or finding it hard to control your anger.

- If you always feel frustrated and unimportant after dealing with your boss or other people in power.

- If you feel you have no power over your life.

Alcohol and drugs

Anyone who has been a parent knows it's not an easy task. When things get on top of you, turning to drugs and/or alcohol will not provide the help you need. The effects of drugs and alcohol on your health and the way they affect your judgment are well documented. You are not looking after yourself if you take illegal drugs or overindulge in alcohol. Your ability to operate effectively as a responsible parent can be significantly affected. If your doctor prescribes drugs for a medical condition, ask how they will affect you and your ability to look after your children. If you already have difficulty coping, tell your doctor. If you have a problem or someone close to you has a problem with drugs or alcohol, seek help. Call one of the help agencies listed on this website and take the first step to improving your and your family's health and well-being.

Children – what is naughty anyway?

Children come into the world embarking on a voyage of discovery. As captain of the ship, you can plot the course with care or let the ship drift wherever the sea will take it. Of course, even adults never stop learning, but a young child is full of wonder at the world and what it has to offer.

Along the way, there is pain and sorrow, but for a young child, there is often confusion as well. Why are they being told they are "naughty" for wanting to touch some new discovery on a supermarket shelf, or for getting into the cupboards? For older children and teenagers, with independence come choices.

Sometimes the choices will be mistakes, but if they are treated as mistakes and not "bad" behaviour, something will be learned from the experience. In the early years, children's absorbent minds are soaking up information, not only from their physical environment but also from those closest to them - most likely you as the parent.

We should not blame children for wanting to make discoveries. They will make mistakes along the way, as we all do, but we must be there when they make them, so they will learn from those mistakes. It doesn't mean we should simply let them do whatever they want - but we must be their guides, not their masters. It is normal for young children to:

- Get into cupboards and take things out.

- Leave toys all over the house.

- Wet or dirty their nappies or pants.

- Refuse to eat.

- Play with the dials on the television and other appliances.

- Refuse to share.

- Be messy.

- Jump on the furniture.

- Refuse to go to bed.

- Have temper tantrums.

- Unpot the plants.

- Scribble on books and the wallpaper.

- Spill food.

- Fight with brothers and sisters.

It might be frustrating when these things happen and we are busy or stressed, but they will happen nonetheless. How we react is important. Keeping calm and recognising that our children are not being "naughty", but that their behaviour is normal (though also at times inappropriate), is the key. When we react with anger and aggression, we show our children this is how we deal with stress. If this is how we have always reacted, we might be pleasantly surprised by children's behaviour when we talk calmly with them.

Be prepared

Knowing that our children are going to do things that annoy us or are inappropriate gives us a head start. In the beginning, at least, we are smarter than they are. We can be prepared and outwit them. Our home is where they will spend most of their time.

When babies arrive, we might have a bassinet or cot for them to sleep in and a room decorated. As they grow older, there might be a highchair, but once they are past the toddler stage, they are often expected to cope in the big people's world. Providing child-size furniture can make a difference. Children who cannot see what they are doing at the handbasin, or have to mess up a kitchen table when they want to draw can get frustrated and angry.

They want to be creative and they want to do things for themselves, but if we don't prepare the environment, we are looking for trouble. Consider getting a few items that will give your child a sense of independence and that you don't need to use yourself. Some of these things can be bought cheaply at garage sales and secondhand stores:

- A child-size table and chair for reading at, drawing, painting, eating at - something that can be messed up.

- A small step or stool that a child can easily carry around so they can reach the things they need (keep those things you don't want them to get out locked away or up high) - for going to the toilet, at the handbasin, at the kitchen bench, to reach books etc.

- A small wardrobe or cupboard so children can get their own clothes in or out.

- Low shelves for toys and books.

- Make sure the cot or bed is low enough for the child to get in and out - try taking the legs off a normal bed and keep the base off the floor with solid blocks of wood or clean bricks.

Know that children will naturally get into mischief, be prepared by distracting them, keeping things out of their reach, or giving them alternatives. If they get into cupboards, childproof the latches or put rubberbands around the handles so they can't be opened by young children. Try putting old pots and pans in a toy box or a cupboard in the child's room. If they leave toys all over the house, make a routine or game of picking them up at a set hour. Make sure they have a toy box or shelf for toys. If they play with the television and other appliances, give them an alternative, such as an old radio, they can play with in their room. Make sure it works, so they don't become easily frustrated with it.

If they are messy, put paper down first and restrict the available space. If they jump on the furniture, let them have cushions or bean bags in their room. If they have temper tantrums, put them somewhere safe until they cool down on their own.

If they unpot the plants, keep them out of the way or let them help you repot them. They are less likely to want to undo their own work. If they scribble on books and the wallpaper, let them scribble on old paper at their table. It doesn't mean you have to accept that it's alright to do some of these things. Children still need guidelines and to know that what they are doing is inappropriate.

Set the rules for children

It is up to you to establish the rules you want your child to stick to. For young children it can be quite straight-forward, for teenagers you will need to provide some opportunities for them to make their own choices and learn to take responsibility for their behaviour.

Some parents use rules to control their children and to exert their power. These parents are likely to lay down the law and punish misconduct often. They are also likely to show little affection for their children, because it might seem that they are "soft". Others let their children do almost as they please. They probably don't show any feelings of anger or even irritation.

Without guidelines and discipline from parents, children are likely to lack direction and self-discipline. Ideally parents will set limits to behaviour, and negotiate the rules and the consequences. They will listen to children and observe their behaviour so they might better understand why they sometimes misbehave. Some parents set too many rules and find themselves saying "no" all the time. Their child will always be "naughty" because they are always breaking the rules. When they get the tag of the "bad girl" or "bad boy", they can live out the role, believing they have nothing to lose because they're always breaking the rules anyway. Be realistic about rules, so you can "pick your fights".

Choose the important rules, make a list and keep them to a minimum. Is it really important if children have their elbows on the table? Involve your child in the process - you might be surprised at how even young children can accept rules when they feel they have "negotiated" some of them. Explain them clearly, then stick to them.

Talk to your partner about the rules, too, so you can both be firm and consistent. Don't set things up for the rules to be broken. As mentioned previously, keep things out of the way if you don't want children to have them. If they can't get them, they can't be tempted to break the rules.

Letting go sometimes

Having rules does not mean keeping a tight rein on what our children do. We all want the best for our children, but we must let them be individuals, make their own mistakes and enjoy their triumphs. We can help them through life by:

- Letting them help with some of the things we do.

- Letting them choose their own activities some of the time.

- Letting them choose their own friends.

- Hearing what they have to say about things - this does not mean you will always let them have things their own way.

- Accepting some of their likes and dislikes.

- Being willing to compromise sometimes.

- As they grow, giving them tasks and responsibilities.

- Understanding that there are a lot of different ways in which young people say who they are.

- Understanding how important the views and approval of their friends are.

- Appreciating and enjoying who your children are - they won't be the same as you.

- Standing by them through troubled patches.

- Celebrating young people's successes, however small they are.

What our children say

Who better than our children to guide us in our efforts to be better at parenting. Perhaps we should listen more to what they have to say about us. The following suggestions, contained in a leaflet produced by the Office of the Commissioner for Children, give some interesting comments from primary and intermediate-age children about how adults could help them be well behaved.

- Talk things over with me.

- Spend time with me.

- Listen to me and respond.

- When I am angry, let me cool down.

- Don't put me down, tease me or insult me.

- Be fair.

- Be sure I understand.

- Show me what you want.

- Show me you like me.

- Keep your promises.

- Don't hit or abuse me.

- Don't expect me to do things I can't do.

- Don't scream at me - just tell me.

- Notice when I behave well, praise me and give me rewards.

- Say you are sorry when you get things wrong.

- Don't get too angry.

- Give me help when I need it.

- Don't overreact to my mistakes.

- Notice me.

- Let me have my way sometimes.

- Don't have favourites.

- Meet me halfway.

- Have a sense of humour.

- Understand me.

- Give everyone a say.

- Encourage me.

- Talk over problems.

- Set a good example.

- Be firm when you need to be, but don't be nasty.

- Don't treat me like a baby.

The supermarket dilemma

Supermarkets have a classic environment for parent/child public confrontations. How many times have you found yourself wondering what to do with a screaming child as you try to do your shopping? Or wondering what to do when you see a parent abusing a child in the supermarket aisle? Children need to be kept occupied with activities when they are out shopping. Their natural tendency is to move, touch and explore. The very reason that supermarkets can cause such stress - that there is so much to distract children - can be used to parents' advantage.

Try giving children responsibility for some aspects of the shopping, or play shopping games. Get them to choose the best apples or cheapest tomatoes, or see how many products they can find that carry a particular brand name. Who can see the toothpaste first? If the child can read, let them tick off your grocery list.

Encourage children to participate by talking about what is happening around them and thinking about the chore you have to complete. Take a favourite book or toy, or a piece of fruit to keep them distracted. Read the book (or tell a memorised story) at the checkout and let the child help with some of the verses. Play "I spy" and get the child to guess what you see at the checkout.

If you find items at the checkout designed to entice children, ask the supermarket to remove them and put them on the supermarket shelves, where you can avoid them if necessary. Don't get upset about behaviour that is not going to hurt the child or someone else. Ignore it if it does not embarrass you or bother other people.

Praise good behaviour and point out good behaviour in other children. Stop bad behaviour immediately and make sure the child is aware that you will not tolerate it in public. If they have a temper tantrum, leave your trolley with staff or an obliging shopper and take the child out of the store to a quiet place. Tell the child that the behaviour is inappropriate and wait until they calm down. If necessary, go to the car with them and wait it out. Then ask if they are ready to behave properly. Before you set out, consider whether you really need to take the child. If they are tired or irritable already, leave the shopping until a better time or leave them with a babysitter.

Make sure they eat before you leave, so they won't pester you for treats. Discuss the behaviour you expect when you go shopping. Consider a small reward that you might buy as you leave the store, or discuss some activities you might do on the way home. If you are in a two-parent family, try to time your shopping so both parents can join in. One can shop while the other keeps the child occupied. Shopping with a friend can help keep you distracted and more relaxed. If the friend also has children, discuss your strategies with them. It can be fun to compare how your respective children react to different ideas.

When you see it happening

It's no fun seeing a parent hitting their children or yelling at them while shopping. Do you ignore it or intervene? If you decide to intervene, what are you going to do or say? Remember first, that the parent is probably acting that way because of some kind of stress. If you step in and tell them what a bad parent they are, you are likely to cop a fair bit of abuse yourself, and the child could get the blame for the incident. It might be better to offer some assistance to the parent. Suggest that you hold the child or look after them for a couple of minutes while the parent gets at least some shopping done on their own or gets the chance to cool down. Such an approach recognises the parent's stress and indirectly offers some sympathy.

Use words that convey sympathy for the parent's plight. "Your child is really making it difficult for you - can I help?" would be a good way to start. Sometimes it will help if you simply strike up a conversation to divert the parent's attention until everyone has calmed down. If you work in a store where you see a parent hitting or abusing a child, advise them that the store is a safe environment where such behaviour is not condoned. Obviously, if a child's well-being is directly at risk because of a beating or severe verbal abuse, step in to stop it immediately and notify the store staff. They should then call the Police to have the matter dealt with.

Child abuse

Our rates of child abuse are among the highest in well-off countries. On average, one NZ child dies as a result of abuse every five weeks. Most of these children are under five years and the largest group is under one year. In the year to June 2016, there were 13,598 children for whom reports of abuse and neglect were substantiated.

In a crisis, dial 111 and ask for the Police. If your children are in immediate danger from another family member, a visitor or intruder, look for safety first. Run outside or head for a public place, scream for help or call the Police. Emergency 111 calls are free from all telephones, including payphones and cellular phones. If you are a neighbour or other witness to violence or other abuse, you have a responsibility to report it. It is a crime and the Police will react accordingly. They ensure the safety of the children.

If you suspect your own children or those of a family member or a close friend are being abused, find out what you can about the family’s present situation. Talk to the parents and listen for any clues as to whether they feel they have particularly difficult problems. See how they react to their children and how their children react - is there a lot of yelling and threats, do the children look fearful? Can you encourage the parents to seek help? If they agree to get help, follow it up. If you are not sure what to do, talk to one of the agencies under the Directory tab in the top menu.

They have trained staff who can advise you what to do or make discreet inquiries about the victim’s welfare. If you genuinely believe children are being harmed, call the Police, or Oranga Tamariki service immediately. Children need special help because they are often unable to take action to keep themselves safe. A Police officer or social worker can then take appropriate action to protect the child. If you merely suspect abuse is occurring - you might have heard yelling and slapping from next door, a child crying - should you report it? If you are not sure, contact a help agency. You can talk confidentially with them about what you know.

They will probably have a better idea of whether abuse is occurring and will know what can be done to help. People, especially those not close to a victim, might be reluctant to report violence or abuse because they feel it is none of their business or they might be wrong. However, children have a right to be protected from harm - you might be their only hope of changing their circumstances.

The desperate face of a two-year-old boy peering from his bedroom window set off bells of alarm that led to the rescue of a toddler surrounded by filth and isolated from the outside world, an Auckland court was told today. The West Auckland boy was found covered in faeces and imprisoned in his room so his mother, who worked as a stripper, could hit the town at night. Neighbours said the boy was violent, spoke in grunts and went through their rubbish like a dog. A neighbour, seeing the boy's face at his window in October, dialled 111 for help. Yesterday, the 23- year-old mother, who has name suppression, sobbed in Henderson District Court when she was convicted by Judge Coral Shaw of wilful neglect...." NZ Press Association report, December 12, 1997.

Abuse and neglect of children in the family is a serious, ongoing problem in New Zealand. High profile cases are greeted with revulsion by most parents, but they still occur with uncomfortable regularity. Abuse is not usually random, but occurs on a regular basis that gets worse over time. It is not defined as just physical attacks or sexual abuse – it can include emotional or psychological acts that are designed to exert power and control over children. Abuse can be:

- Physical – sometimes it does not cause bleeding or leave bruises, but it is enough to cause fear of physical harm in a child. When violence is used, a child fears that next time it will be worse.

- Sexual – rape or the use of force or coercion to induce a child to engage in sexual acts against their will.

- Emotional – it can be constant put-downs and name-calling, intimidation and harassment; things that make children feel bad about themselves.

It is likely to include yelling and threats of physical violence, or threats designed to make children fearful. Looks, actions and expressions might be used to instil fear. Items valuable to a child might be smashed or pets harmed.

- Isolation – a child might be isolated from friends, often because their friends are made to feel unwelcome in the home.

- Neglect – depriving children of necessities such as food, shelter, supervision appropriate to their age and essential physical and medical care.